For the last 8 years, I have been a Field Training Sergeant. It is truly a pleasure knowing that I am having an impact on the future of my police department by training these new leaders. I see this responsibility as a vital one. If I do not do a good job, I am not just affecting that new sergeant, but every officer that serves on his or her squad.

Just so we are on the same page, here is how my department handles sergeant training. Sergeant field training is a 5 week process – 2 weeks with one training sergeant, 2 weeks with a different training sergeant, and then one final week back with the first training sergeant. At the end of each shift, the Field Training Sergeant completes a daily observation report (similar to FTO) that summarizes and scores everything the prospective new sergeant did throughout that shift. While writing these daily observation reports, I have noticed that there are certain bits of advice that I seem to be repeatedly writing for every sergeant I help train.

So, here are my 10 tips for new sergeants . . .

- Successful sergeants spend 80% of their time working with people and 20% doing everything else. Sergeants that fail to inspire, have a poor squad culture, and breed negative officers focus more on everything else rather than people and building relationships.

- Successful sergeants find ways to teach their officers to be adaptive decision-makers; not robots that only understand how to solve problems with checklists. When opportunities present themselves, sergeants explain their process for making difficult decisions and everything they took into account. Then, when their officers face similar situations they have been taught to apply their own similar process.

- Successful sergeants never waste briefing time. There is always something that could be discussed, debated, trained, or learned in briefing. This is one of the few opportunities when sergeants have their entire squad’s attention at the same time; make the most of it.

- Successful sergeants understand that policing is a complicated profession. Both sergeants and their officers are going to make mistakes at some point. Do not hide mistakes, share them openly and turn them into learning opportunities focused on improvement. Mistakes are fine, just don’t make the same one twice.

- Successful sergeants recognize, reward, and promote good police work by their officers. They use whatever methods are available at their department to make this happen anytime an officer goes above and beyond. Not only does this create a more positive culture, but it also spurs on more officers to look for opportunities to go above and beyond. What a sergeant rewards will be repeated.

- Successful sergeants have a vision of the culture they want to have on their squad. Squad culture is defined as the conglomeration of your officers’ actions, attitude, and effort. If you asked another sergeant to describe your squad in 4 words, what words would they use? That is your culture. If you don’t like those words, do something about it.

- Successful sergeants do not lead from their desks. They get out on the road with their officers and find ways to serve them throughout each shift. They never believe themselves to be too good for the “grunt” work of being a patrol officer; they get in there and get their hands dirty occasionally.

- Successful sergeants recognize that their actions, attitude, and effort tell their officers what is important to them. If a sergeant speaks negatively about their schedule, some situation at the department, or some aspect of the job, then don’t be surprised when the officers have that same opinion or are representing that opinion openly. Negativity breeds negativity.

- Successful sergeants know what they do not know, then they find ways to compensate for those areas. If they are not good at tactical situations, they talk to the department’s SWAT officers about various scenarios and how they would handle them. If they are not good at traffic or investigations, they build relationships with motors or detectives that are respected. The most important aspect of this tip is that a sergeant never fakes knowledge and gives bad advice to an officer. This will kill their credibility. If an officer has a question that the sergeant does not know the answer to, the best thing they can do is say, “That is a great question, I don’t know, but I know someone who will. Standby and I’ll call you right back.”

- Successful sergeants never allow themselves or their officers to stop learning. The minute a sergeant thinks they know it all is the moment they begin sliding towards mediocrity. A sergeant values training and realizes that the more training they can get for their officers, the better their officers will be on the road.

Got a tip you would give to a new sergeant?

The mission at Thin Blue Line of Leadership is to inspire law enforcement supervisors to be the best leaders they can be by providing positive leadership tactics and ideas. Positive leadership and creating a positive squad culture are on-going commitments that must be nurtured and developed over time. Thin Blue Line of Leadership is here to help.

Please do not hesitate to contact us if you have ideas to share or suggestions for improvement. Your thoughts or comments on this blog are always appreciated either below or on our Facebook page. You can also follow us on Twitter at @tbl_leadership.

Continue saving the world one call at a time and as always, LEAD ON!

The second myth of accountability is that accountability is only something I do to other people. Specifically, the people that work on my squad or unit. If my view is that accountability is an external process of me holding others to my expectations or those of the department, then I am creating a culture of “them” and “they.” With this idea of accountability, I believe I must hold them accountable at all times and attempt to control their performance towards my expectations. This often comes across as micromanaging to those being led and to me it feels as if my entire job has become running around putting out fires all day. To those I am holding accountable, their perspective becomes one of contempt and I have now become part of the infamous “they.” The generic pronoun used to describe those higher in power within an organization when we feel there is not a choice in whatever matter is at hand. Ultimately, this style of accountability is only sustainable for as long as the leader can manage the energy to keep it up and are physically present around those they are “leading” to enforce their expectations. Once the leader becomes too tired to keep it up, they retract to the confines of their office to hide because they just cannot manage the level of effort required to constantly hold six to eight people constantly accountable. Worst of all is that none of those on the squad or unit have ever learned how to hold themselves accountable to these expectations because the boss has always done it for them.

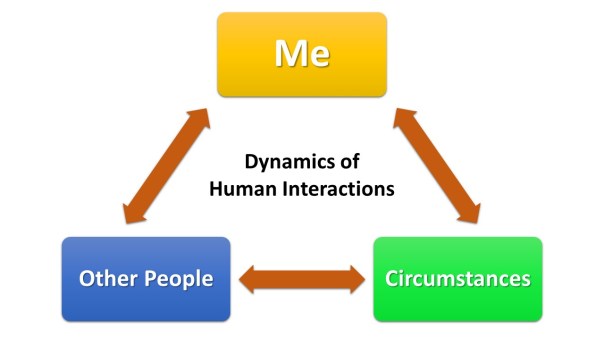

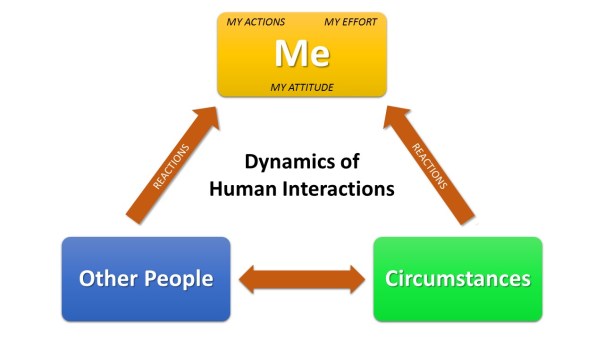

The second myth of accountability is that accountability is only something I do to other people. Specifically, the people that work on my squad or unit. If my view is that accountability is an external process of me holding others to my expectations or those of the department, then I am creating a culture of “them” and “they.” With this idea of accountability, I believe I must hold them accountable at all times and attempt to control their performance towards my expectations. This often comes across as micromanaging to those being led and to me it feels as if my entire job has become running around putting out fires all day. To those I am holding accountable, their perspective becomes one of contempt and I have now become part of the infamous “they.” The generic pronoun used to describe those higher in power within an organization when we feel there is not a choice in whatever matter is at hand. Ultimately, this style of accountability is only sustainable for as long as the leader can manage the energy to keep it up and are physically present around those they are “leading” to enforce their expectations. Once the leader becomes too tired to keep it up, they retract to the confines of their office to hide because they just cannot manage the level of effort required to constantly hold six to eight people constantly accountable. Worst of all is that none of those on the squad or unit have ever learned how to hold themselves accountable to these expectations because the boss has always done it for them. The truth about leadership accountability is that it is all about ME. It starts with ME. It sustains with ME. It grows with ME. It can be ended by ME. The concept of anything in leadership being “all about me” is a colossal departure from 99.9% of what I read and hear about good leadership, but when it comes to leadership accountability it truly is controlling MY actions, MY attitude, and MY effort that dictate my application of accountability. Leadership accountability is an inside out process. It is through internal accountability that I set the proverbial bar or expectations. Those I am leading see what I am doing, how I am doing it, and most importantly I explain why I am doing what I am doing. As the example is set, then I have earned the right to set external expectations of those I am leading because they know that I am not and never would ask them to do something I am not doing or willing to do myself. In other words, I must exemplify accountability before I can ever expect it from those I lead – that is leadership accountability.

The truth about leadership accountability is that it is all about ME. It starts with ME. It sustains with ME. It grows with ME. It can be ended by ME. The concept of anything in leadership being “all about me” is a colossal departure from 99.9% of what I read and hear about good leadership, but when it comes to leadership accountability it truly is controlling MY actions, MY attitude, and MY effort that dictate my application of accountability. Leadership accountability is an inside out process. It is through internal accountability that I set the proverbial bar or expectations. Those I am leading see what I am doing, how I am doing it, and most importantly I explain why I am doing what I am doing. As the example is set, then I have earned the right to set external expectations of those I am leading because they know that I am not and never would ask them to do something I am not doing or willing to do myself. In other words, I must exemplify accountability before I can ever expect it from those I lead – that is leadership accountability.